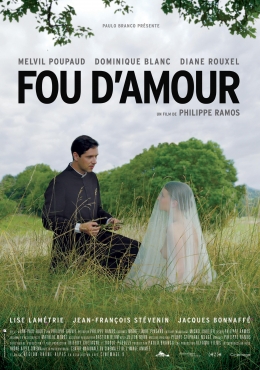

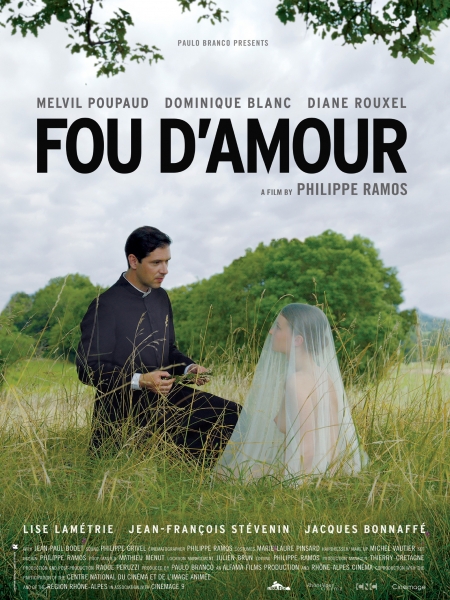

1959. Guilty of a double-murder, a man is beheaded. At the bottom of the basket that just welcomed it, the head of the dead man tells his story: everything was going so well! Admired priest, magnificient lover, his earthly paradise seemed to have no end.

Available in

DVD

DVD

Language:

French

Subtitles:

English

Disc features:

TOUS PUBLICS | 16/9 compatible 4/3 | 1.78:1 | Color | Dolby Digital 5.1| DVD9

Discs:

1

Cast

MELVIL POUPAUD - The priest

DOMINIQUE BLANC - Armance

DIANE ROUXEL - Rose, the young blind girl

LISE LAMÉTRIE - Lisette

JEAN-FRANÇOIS STÉVENIN - The priest of Mantaille

JACQUES BONNAFFÉ - The Great Vicar

JEAN-PAUL BODET - Félix the postman

VIRGINIE PETIT - Mademoiselle Desboine

NATHALIE TETREL - Jacqueline la laitière

VANINA DELANNOY - Solange the cousin

ANAÏS LESOIL - Odette

Crew

Direction and Screenplay Philippe Ramos

Produced by Paulo Branco

Assistant Director Bastien Blum

Sound Philippe Grivel

Original Music Pierre-Stéphane Meugé

Cinematographer Philippe Ramos

Costumes Marie-Laure Pinsard

Hairdresser/ Make up Michel Vautier

Set Design Philippe Ramos

Prop Master Mathieu Menut

Location Management Julien Brun

Editing Philippe Ramos

Production Manager Thierry Cretagne

Production and Post-production Raoul Peruzzi

An Alfama Films Production

and Rhône-Alpes Cinéma coproduction

With the participation of the

Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée

and of the Région Rhône-Alpes

In association with Cinémage 9

Philippe Ramos - Filmography

FEATURE FILMS:

FOU D’AMOUR

2015, 105 mn

With: Melvil Poupaud, Dominique Blanc, Diane Rouxel, Lise Lamétrie, Jean-François Stévenin, Jacques Bonnaffé

THE SILENCE OF JOAN

2011, 90 mn

With: Clémence Poésy, Thierry Frémont, Mathieu Amalric, Liam Cunnimgham, Louis-Do de Lencquesaing, Jean-François Stévenin, Johan Leysen.

Cannes Film Festival 2011 - In Selection at the Directors’ Fortnight

CAPITAINE ACHAB

2007, 94 mn

With: Denis Lavant, Dominique Blanc, Jacques Bonnaffé, Jean-François Stévenin, Philippe Katerine, Carlo Brandt, Hande Kodja, Mona Heftre.

Award for Best Director at the Locarno International Film Festival 2007

FIPRESCI Prize at the Locarno International Film Festival 2007

AFAREWELL HOMELAND

2002, 80 mn

With: Françoise Descarrega, Philippe Garziano, Frédéric Bonpart.

Jury Special Prize at the Albi Festival 2003

SHORT FILMS:

CAPITAINE ACHAB 2003, 22 mn

NOAH'S ARK 1999, 57 mn

ICI BAS 1996, 26 mn

VERS LE SILENCE 1995, 35 mn

MADAME EDWARDA 1992, 20mn

Philippe Ramos

Interview with Philippe Ramos

The case of the priest of Uruffe, a sordid news story from the fifties, was already the inspiration for one of your short films. Why did you decide to work again on that story?

In Ici-bas, the character of the priest had all the anxieties of the world on his shoulders, and the film had a suffocating seriousness: the dynamic and charming side of the murderer was put aside.

I had a feeling of something left unfinished. With Fou d’amour, just like a painter who goes back on an element of his painting to reveal new aspects, l reworked « my canvas ». This time, happiness and pleasure would come before destructive madness. I used a lighter, even comical tone for this film, before gradually changing the colors in small touches to create a gradation of atmosphere and emotions that turns into intense black and tragic.

When you worked on the adaptation, did you stay true to the news story?

I kept some elements like the double murder, the football club, the small theatre… Then, after changing all the names of the characters and places, l gave free rein to my imagination: in fact, the young victim wasn’t blind, the priest wasn’t executed by guillotine... etc.

Since the real priest wasn’t executed by guillotine, why did you go for that?

I got inspired by my producer’s feedback on the script and l had this idea of the story being told from a voice coming “from the dead”. Fou d’amour would be haunted by a grim storyteller: the severed head of a priest… Which is both funny and horrible. I had therefore a key element that showed perfectly the comical and tragical aspect that l wanted to give to the film. The choice of the execution was guided by the narrative – l didn’t want to talk about the death sentence. That issue, just like the issue of priests’ sexuality, are maybe underlying themes, but it’s not the point l’m trying to make. From a historical and social point of view, what interests me above all is to dig inside the intimacy of human beings, show their true colors, their desires, and their madness. For that reason, l’m more of a “portrait filmmaker”, rather than a filmmaker who examines the big issues of society.

Speaking about literature, Walter Benjamin once said that the storyteller is the one with whom the reader takes refuge in a brotherly way. Do you agree with that point of view?

Absolutely. I should admit that l used this brotherly feeling, to try and insidiously lead the viewer into an abyss. Which is a perverted and manipulative game… But l believe in the good meaning of word, in the Hitchcockian meaning of the word. We’re swamped by the nice words of this man, who acts like a victim, who’s well spoken, who has wit, we’re leading ourselves into a very dark destination: the troubling immensity of human madness.

Would you say that the storyteller, the severed head, is the main character of the film?

Yes… And for this to work, the talent of Melvil Poupaud on the voice over has been crucial. His smooth elocution, his own way of making words sound full of flavor, makes the viewer easily fall under his charm. We recorded all the voice over “on location”, during the shoot. Melvil was therefore completely immersed in the character when delivering the text. Often the recording took place during weekends. At the beginning of the week, he would put his cassock back on to immerse back into the small world of the priest. To play this multi-faceted character, Melvil managed to be both handsome, and ridiculous, intelligent and mediocre, gracious and pathetic. He managed to embody all these contrasts on set, with subtlety and generosity.

By his side, we have many of the same actors that you’ve worked with previously, including Dominique Blanc.

Yes, l wanted to work with her again, just like with Jean-François Stévenin and Jacques Bonnafé. A sentence from the voice-over, cut in the edit, said regarding the character played by Dominique: “How could l leave a woman with such elegance of mind?” This phrase “elegance of mind” sums up perfectly what l think of this great actress and her refined performance. Even when delivering the most mundane lines from day-to-day life, Dominique is capable of huge intensity on every single move, every single intonation. For me, this mixture of seeming nonchalance and power makes all the beauty of her performance.

You’ve never worked with Diane Rouxel before. How did you meet her?

I met her thanks to Isabelle de La Patellière, who’s her agent. Diane had just finished working on Larry Clark’s film “The smell of us” and was about to play in Emmanuelle Bercot’s “La tête haute”. To play a blind character is a difficult thing. During a trial, Diane realized that she could move her eyes in different directions and managed to have very specific eye gaze positions. This “technical” find has been determining for us because it’s given us a realistic basis for the work we have to achieve. For the rest, her youth, beauty, this form of innocence that comes out of her, have perfectly contributed to the image that the priest has of her: for him, she’s an icon.

In order to approach your very specific way of working, l think it’s crucial that you tell us how you started making films.

During secondary school, while l didn’t have any particular links to film (l wanted to work in comic books), a teacher asked us to make a cartoon. I absolutely loved the experience so l bought a Bauer Super 8 and started making films. I didn’t have a cinephile culture. I was making comic books that l tried to represent “for real” with schoolmates that suddenly became actors. I did a dozen of Super 8 films, both shorts and features. So, for many years, l was working on my own within my home-made factory.

The fact that today you are the camera operator or editor on your films is in direct consonance with that “home-made factory”?

Yes, there’s no doubt that all those Super 8 years are deeply rooted in me. Today, even though l surround myself with valuable collaborators, l also need to shape the material in order to understand it and tame it. So, l’m the one deciding on set design, l work on the visual identity of the film, l edit. This way of working, from my amateur filmmaking years, is a real need, like those painters that mix up pigments of colors themselves even though they could have specialists do it. By doing so, those painters find a form of concentration, and even inspiration for some, that will enhance their creation. It’s exactly the same for me.

When you speak, you often refer to the painter’s work and painting.

Strangely enough, I am much more inspired to make films by looking at paintings, rather than watching other films… As if it was a bigger trigger of desire. Themes, characters, gestures, colours, forms, everything inspires me in painting and encourages me to take that path. I could almost say that my true mentors are not filmmakers, but painters. By the way, when l studied history of art, l used to say that it’s the best film school in the world. As if by learning how painters worked, how they live their art, l would learn how to make films… Maybe that wasn’t wrong after all!

You storyboard your films… Yet again, it’s about drawing.

This small illustrated book is a really valuable piece of work for me. It has all my choices for writing, set design, visual identity, editing… It’s a specific form of the film, a pre-existing, constructed structure, which the actors inhabit, and therefore give life to. The storyboard allows me to visualize and compose, clearly, the style of the film. A style where l’m looking to enhance breaking points and contrasts. By the way, this intention to confront things, to break up, oppose, is there, at every stage of my work, from script to the editing. You just need to see how the film is built: in two pieces… Head and body!

You talked about the different facets of your character, you just mentioned a divided form, why insist so much on multiple or broken lines?

Maybe because it seems to me that they are a true reflection of life.

Press review

« Fou d’amour », itinéraire d’un prêtre meurtrier

« Fou d’amour »

Un pretre assassine sa maitresse enceinte. Grivois et grinçant.

« Fou d’amour » L'istoire du curé d'Uruffe défraya la chronique dans les années 1950. Un conte très insolent, ou une simple grivoiserie insignifiante?